And Still It Was Bittersweet

Martin Elkort, an enormously talented artist, was not only a street photographer, an illustrator, a writer with numerous books and magazine articles to his name, a food critic, a friend, a mentor and teacher to many—he was my father. He left behind the arts and worked in the travel industry for most of his adult life to support his family, but when he retired, only then did he once again pick up his camera and begin to photograph in the same style he was known for in the late 1940s in New York City. And with his renewed focus came the opportunities to exhibit his work.

When I recognized the revived interest, I realized my father lacked the skills to organize and promote his artistry. When I began to see what was needed, I knew I could help. After twenty years working as a video biographer, helping families and companies tell their stories and leave lasting legacies for their future generations, I, his daughter, had the exact skills he was missing. I excel in project planning, photo scanning and archiving, large volume archive indexing, and storytelling. And I knew that working with him would provide both of us the opportunity to not only spend more time together but also to achieve a common goal of finding a wider audience for his art.

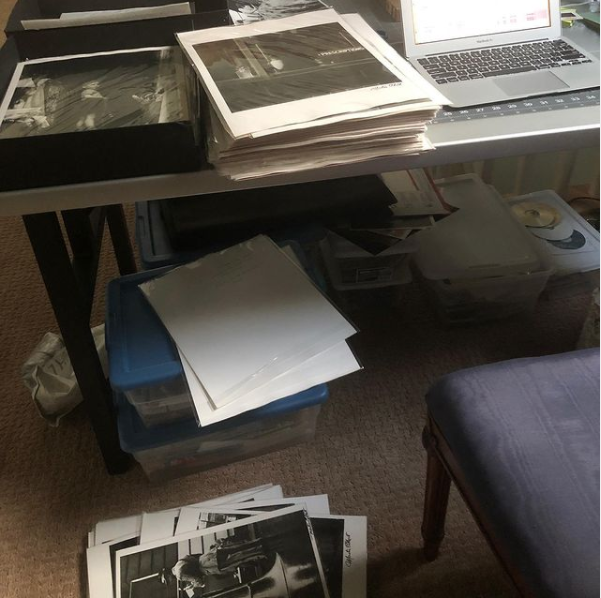

During the early years, we built his website (martinelkort.com), began high resolution scanning of his negatives, created an inventory of silver-gelatin prints, organized gallery shows, produced a book of his photographs of children (Children: Behind the Lens), and created and developed press opportunities. My father’s photography came second to the fun I had working with him on such a large project. I know Martin cherished the time we spent together and was grateful that I would spend my time with him. He also found a renewed sense of passion for making sure that his photographs, his legacy, received even more exposure. As much fun as we had, it wasn’t always easy. Marty’s “stuff” was disorganized and thrown together in numerous boxes and file cabinets. The attention he gave in the taking of photographs did not carry over into their management. But over the years, we built all his “stuff” into a well-organized and sizable archive.

In November of 2016, Marty passed away. It wasn’t long after that, at least for me, that the fun went with him.

Fast forward to March of 2020. Covid had us all in lockdown, but thanks to Zoom, we had the opportunity to participate in groups that may have been more difficult prior. I have been a member of the American Photographers Archive Group (APAG) for close to ten years now. Based in NY, before Covid, I had managed to attend only a few virtual sessions. But last year, I started going to a weekly Zoom meeting, and it was in these meetings that we discussed what photographers and archive managers were up to. In a small chat room after the main presentation, I shared my history with Marty’s photographs, and that I wasn’t sure where or how to move forward. That conversation led to an invitation from the Dolph Briscoe Historical Center for American History, which has forever changed my life.

The Briscoe Center is an Austin-based organization that collects, preserves, and provides access to materials relevant to United States history. The center operates within the public services and research components of the University of Texas, at Austin. As one of the largest historical archives in the US, their Photography Collection holds more than five million photographic images from the late 1840s to the present, including the archives of leading photojournalists.

Prior to arranging the photos, letters, and other documents to send to Briscoe, I orchestrated five museum acquisitions: The Jewish Museum in NYC, The Museum of the City of New York, The Norton Museum in Palm Beach Florida, The Columbus Museum of Art, and the Los Angeles Public Library. All significant and respected institutions. Afterwards, I spent a full year creating a more complete inventory of all of Martin’s photos and documents prior to sending them to Briscoe.

This past week, Alison Beck, the Director for Special Projects at Briscoe came to my home to pick up everything and travel it to Austin. After she left, I walked around the empty den, looked in the empty closets, and had such mixed feelings. I am so proud of my father’s body of work and the fact that his legacy will now live on in perpetuity. It will forever be available to museums, historians, writers, and film makers. Also, this legacy will no longer be my responsibility. For that, I am greatly relieved. Being responsible for the physical contents has always been a concern. I no longer need to worry about a hurricane ripping off the roof and waterlogging all his prints. Or any other doomsday scenario I could think up. In addition, and on a personal note, I have opened up a world of free time which can now be spent on some of my own hobbies and pursuits. But also, watching those boxes drive off the other day left me faced with a concrete ending of a part of my life, a part that gave me such a sense of joy and accomplishment.

I think I should have taken photographs of the piles of boxes, then the boxes sitting in the car and, finally, me waving good-bye. But when the boxes were leaving, my emotions didn’t allow me to get outside of myself enough to even think about recording this moment.

But I sure did feel my dad standing beside me that day, as we both watched his legacy drive off down the street.

Stefani Elkort Twyford

August 10, 2021

Stefani,

The Briscoe Center is honored that you selected us to preserve your father’s legacy and make his work available to the public for teaching and research. You have been a pleasure to work with this past year–a bright spot during the Covid darkness. Alison and I are both so pleased that you are now an official part of the Briscoe Center family.

What a monumental labor of love. And yes, the holes left when the labor is done have to be huge. Blessings on all your work, and the gift of your dad’s passions, now ready for others to benefit from.

As I read the final paragraphs of this saga of your life, I am struck by the thought of how much more energy you will now have to pursue the activities in your life. It is a good deed you have done. Now it is time to fly!

Your father’s photography documented his life and times–even when he was focusing on others who were strangers to him. I remember feeling that when I saw the photos you shared with us. And now, the work you did with him, and then after he died, will bring pleasure and a sense of history to future viewers.

I can imagine you looking at the empty drawers, files, etc. Probably wishing he were there in life to see the last journey of his work to a safe and accessible place. Congratulations!

His archives are in the right place, Stephani. Big people leave big holes when they’re gone. I really enjoyed reading your piece and it reminds me I owe myself one about my own father.