Featured in Rangefinder Magazine (January 2007)

In Valleyheart Drive, a sundappled street fronting a culvert in the heart of California’s San Fernando Valley, is an unassuming cottage. It is the home of photographer Michael Richard. He is blind.

With a cherubic face topped by a head of curly, light-brown hair, Richard looks decades younger than his 58 years. He wears dark glasses, and a powerful magnifying glass hangs from a string around his neck, ready for use. This gives him the presence of a Hollywood movie director—not too far from the mark. Before blindness struck, Richard worked as a singer and songwriter.

Richard was born with amblyopia, an uncorrectable “lazy” left eye; bad enough in general, but usually the other, “good” eye can compensate. Then, in 2002, he was diagnosed with a rare choroidal melanoma, a tumor in his good, right eye. After surgery, he became legally blind. He was able to revive his singer/songwriter career through solo acoustic performances featuring songs from his CD. But he could no longer see written music on stage, so when asked to back up and direct other acts, he had to memorize entire shows beforehand.

Now, with only about 10% vision in his left eye, photography, which was always a secondary artistic interest for him, has taken front and center as a major influence and creative outlet.

Recovering from the operation in the fall of 2002, Richard heard of a class in photography at the Braille Institute in Los Angeles taught by Jack Birns, former LIFE photographer and a founder of photography store Birns & Sawyer. Birns was beginning to lose his sight and wanted to show blind people that they could use cameras and take good pictures.

The flashbulb that went off in Richard’s head when he took Birns’ class changed his life. With typical enthusiasm, he plunged deep into photography, while still working to rebuild his career in music. Gradually, photography became more and more important to him. At first he used disposable cameras, because fiddling with the camera’s dials was too difficult. Then he heard of George Covington’s Let Your Camera Do the Seeing, a manual of photography for the blind. After reading the book, Richard began using his manual camera again and bought a 28–70mm lens. With the lens set at 35mm, he set the focal length at f/8 and pre-focused the camera at around 10 feet, giving him a large depth of field. With his camera on a tripod and his lens preset, he was ready to take pictures. “If you use maximum depth of field on the lens, you can pace off the distance and shoot it,” he says.

His routine changed again when he met noted photographer Roger Marshutz, who took an interest in Richard’s work, gave him an auto-focus camera, and suggested he shoot color as well. The autofocus camera liberated him from having to focus in advance, and shooting in color was a new and exciting experience. “Although,” he says, “I tend to see images in black and white.” Today he shoots in both color and black and white, but still prefers the latter.

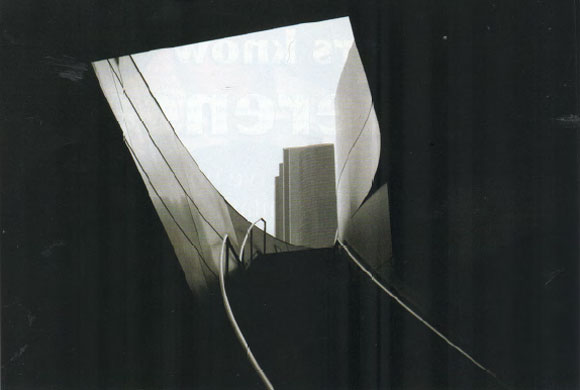

Because Richard can’t tell what people are doing and a crowd is just a blur, he concentrates on forms, often quite abstract. “Go with your strengths,” he says with a smile. His typical photo shoot begins with him deciding on a four-block area of the city. He is dropped off there with his camera and stays strictly within the predetermined area because he cannot move too freely alone. This imposes an enforced discipline; he has to find subject matter within the area chosen. No matter what happens or how “empty” the area appears at first, he is unfazed.

He keeps working, thinking and analyzing until he finds the potential images that are within any area. On a good day, he will shoot for several hours in his chosen area, then get dropped off in a second area, where he repeats the process of finding images. Richard is determined to find subjects no matter where he is and concentrates on analyzing what his perceptions bring.

He looks for totemic images and iconic scenes and depends strongly on inspiration. As he explains it, he “constructs photographs” with what he finds, carefully analyzing what he sees with the limited vision he has left. Then he experiments by changing perspectives, looking up, then down, sampling the scene from varying positions. He will lie on the floor, climb a staircase, and try anything that promises to yield a good image. With a fondness for musical analogies, Richard quotes the avant-garde musician John Cage, who once said he was “giving up control so sounds can be sounds.” Richard says, “I can only control the subject matter to a point, but then I have to let go and follow my instincts, letting the subject dictate how I take the picture.”

The moments fly by while Richard is working. He is happy as he searches for clues and patiently waits for inspiration— for just the right moment. He prefers extemporaneous situations that appear from nowhere. Sometimes he experiments with angles and distances. Other times, he has to wait for the light to be just right. He persists until, like a fisherman angling for trout, he lands his image. He says, “The creative act takes precedence. Music is theme-oriented, and photography can be that way too, in a visual sense. I don’t have to be in control of every aspect of the picture.

Once I learned that, it opened a big door for me. What I do—I try to hone in on my visual themes and let the rest work itself out. You have to believe in yourself, that you will succeed. I feel I am predestined to give it my best.”

There are 1.3 million blind or partially sighted people in the United States, and among them are a sprinkling of photographers. No, that is not a misprint. A blind or partially sighted photographer can often take pictures equal to those of their fully sighted peers. They bring a particular sensitivity to the task.

When considering the blind, one might be burdened with preconceptions, cultural and emotional baggage. The mystique of blindness intrigued many writers, such as Robert Louis Stevenson, whose Blind Pew (from Treasure Island) was the personification of evil. From the blind Greek poet Homer to John Milton, Helen Keller, James Joyce, James Thurber, Joseph Pulitzer, up to contemporary creative people such as Ray Charles, Andrea Bocelli and Jose Feliciano, blindness coupled with talent raises many questions.

Is the talent related to the handicap? Does losing one of the five senses create compensatory strength in those remaining? If they were sighted normally, would their creativity be so extraordinary? Conjure the image of Ray Charles rocking back and forth on his piano stool and belting out his signature song, “Georgia on My Mind.” Charles lost his sight as a young boy. He became dependent on his hearing to navigate the world in which he lived.

Did the hyperdevelopment of his hearing sense create a sensitivity to sound that resulted in his achievements in music? Or did the experience of blindness create in him a desire to triumph over adversity and succeed in a world that judged his handicap?

What motivates someone who is blind to fly in the face of logic and practice an art that depends upon eyesight? There must be easier ways for a blind person to express himself: sculpture, for example. Okay, we understand that someone doesn’t need eyesight to play a musical instrument or write a book, or perhaps sculpt a statue. But the word photography means writing with light, and a photograph is something that must be seen and requires sight.

But a blind photographer? I believe it depends on what blind is. Let’s start with a totally blind photographer: zero sight in both eyes, eternal darkness. Yes, there are even some photographers with zero vision. They depend on input from their other senses and often from a companion who gives them important information. They hear the subject, smell or feel the environment; is it a pine forest, a kitchen with someone baking, a burbling brook? There are many clues. When the subject laughs, or sighs, that is a signal to the photographer to take a picture and an indication of where to point the camera. The companion, acting as surrogate eyes, can direct the photographer, who makes the ultimate decision when to snap the shutter.

The great fashion photographer Albert Watson was born with no sight in one eye, yet rose to the top of his field, taking wonderful photographs for major fashion magazines. He was the subject of a book of photographs entitled (what else?) Cyclops. The term “legally blind” merely adds to the confusion. According to the American Optometric Association: “In the United States, any person with vision that cannot be corrected to better than 20/200 in the best eye, or who has 20 degrees or less of visual field remaining, is considered legally blind.”

Many years ago, I stood at the rim of the Grand Canyon watching the sunset. I blurted to the stranger on my left, “Isn’t that wonderful?” When he turned to reply, I saw dark glasses and a white cane. I suppose he sensed my confusion. He said, “I enjoy being here and knowing what is in front of me. In my mind I see the sunset and imagine what it is like.”

The tragedy of blindness from birth means one has no visual references to rely on—never having seen a flower, a butterfly, a sunset, a mountain or the face of another person. Imagine, if you will, that you just arrived here from another planet and, for the first time, you beheld a butterfly or a flower. What miracles they must seem to be! If you can bring that sense of wonder to bear the next time you take up your camera, you will have wiped your mind clean, like the windshield of a dusty car, and will approach your photography with a new freshness, a new respect. If there is any sad consolation in becoming blind later in life, perhaps it lies in the treasured memories of what once was seen.

Slowly, as I researched this article, the apparent oxymoron of a blind photographer morphed from skepticism to understanding. A blind photographer, through photography, can find a way out, a way to conquer this terrible handicap. If a blind person can take a photograph with merit and beauty, then he or she is no longer blind. Supported by the remaining senses, imagination triumphs, bringing visual beauty to a soul that otherwise would be denied this pleasure others take for granted. This is the stuff of poetry and heroism. When a blind or partially blind person makes a photograph, it can be a powerful statement of courage and strength of will.

And so, I found that meeting Michael Richard not only showed me how someone with a mere scrap of the full, glorious vision most of us enjoy can still take pictures with artistic merit, pictures worthy of gallery and museum viewing. He also taught me, far more importantly, to admire and respect the courage and heroism that he and other blind photographers display daily.

[Editor’s note: Michael Richard passed away on August 28, 2006, due to complications from cancer. He was 58. His creativity and courage will be an inspiration to us all.]

Martin Elkort has been a photographer since age 10. He is a former member of The Photo League, and his photographs are in the collections of the New York Museum of Modern Art, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Elkort resides in Los Angeles, CA, where he continues to refine his craft.