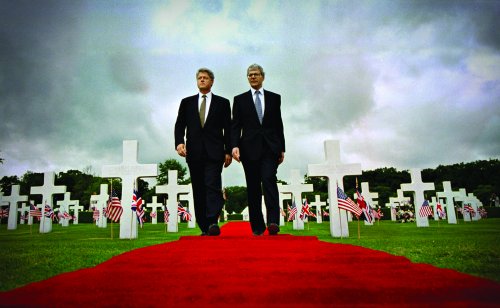

President Clinton and British Prime Minister John Major, right, walk between U.S. servicemen’s headstones during a D-Day anniversary service at the American cemetery in Cambridge, England, Saturday June 4, 1994. (AP Photo/Greg Gibson)

Featured in Rangefinder Magazine (June 2007)

To paraphrase Winston Churchill in his WWII book The Hinge of Fate, when one of history’s doors slams shut, an era ends and a new door swings open. Some doors make loud noises when they open or close, while others are still quietly reverberating. Co-opting Sir Winston’s metaphor for our occupation, the door to the photographic field has recently begun to swing on its hinge.

Gone are the days when traditional film images bulletined daily. Will silver gelatin retire to gather dust in museums, alongside the albumen print and the daguerreotype? Perhaps it’s still too early to say.

President Clinton waves to a crowd of 35,000 people that waited in a downpour for his arrival during a campaign event at Pike Place Market in Seattle on Wednesday, Sep. 18, 1996. (AP Photo/Greg Gibson)

From the laughably jagged images of a few years ago, digital photographs are now so advanced that they compare favorably with traditional silver gelatin prints, and according to some, surpass them in quality and ease of use. Forget the darkroom, with its smelly chemicals that turn your fingernails brown. The new laptop darkroom fits into an attaché case and allows you to develop pictures in broad daylight. While the digital parade marches down all the boulevards of photography, its value is most visible in photojournalism and news reportage, where time is of the essence. Speed is digital’s middle name.

Let’s take a photographer’s loupe and examine the hinges of Churchill’s door analogy. The year 2007 marks the eleventh anniversary of digital’s entry into photography’s mainstream conscience. In 1996, the Associated Press (AP) gave its photographers digital cameras, forcing the issue on the rest of the industry. At that time (prior to 1988–1989), if a photographer was out in the boonies, he had to haul enough equipment for a complete darkroom in the trunk of his car, shoot his assignment, then set up post-processing in a hotel room, restroom or anywhere else nearby with running water. He coped with small sinks, ambient light and other problems. Lock That Door Behind You

For photojournalist Greg Gibson, awaiting the arrival of a hurricane in Atlantic Beach on the coast of North Carolina in the fall of 1984 was all about this type of improvisation. Greg, who was only 22 years old at the time, was working for UPI (United Press International). While he shot photographs of people preparing for the hurricane, he anticipated the job ahead: processing and transmitting the film at the hotel before the hurricane hit. The problem was that Greg had never made a color print before! Since he had all the chemicals and gear necessary, his boss at UPI walked him through the process over the phone.

On the phone, his boss would ask, for instance, “How does it look?” To which Greg would respond, “It’s a little red.” His boss would then say, “Increase the magenta ten points.” Greg was coached step-by-step through making his first color print as a hurricane bore down on the coast.

While all this was nerve-wracking enough, once the film was developed, Greg had to send the images to UPI on a Uni-fax drum transmitter over phone lines so they could go to press the next day. He set up the transmitter, following step-by-step instructions via phone, and began sending his images: 10 minutes for each black-and-white photograph and 30 minutes for each color image. As the hurricane descended, repeated power surges ruined the transmissions, and Greg had to start over again and again. The hotel manager knocked on the door as Greg wrestled with his equipment; he was told that everyone was evacuating and he too would have to leave.

Greg pleaded for more time and the manager left grumbling. He was back a few minutes later, knocking louder, with increasing desperation in his voice. The power surges kept returning, as did the manager. Each time, Greg had to restart the transmission to UPI. Finally, the exasperated manager said, through the door, “I really have to go now, Mr. Gibson. You are alone in the hotel. Please turn out the lights, lock the door and leave!” Finally, with his boss still on the phone, Greg got his images out successfully and beat a hasty retreat as the hurricane winds began tearing the roof off the building. Greg’s images appeared on the front page of USA Today the next morning.

Walk On Through

While news reportage is filled with excitement, surprises and drama, nowadays it emanates from the subject and the location, rarely from the equipment. Digital technology is now so dependable that major disasters caused by equipment or processing are infrequent. Gone are the days when, for example, Robert Capa’s precious negatives of the D-Day invasion of Europe were developed, and in his haste to make a print, a technician hung the negatives too close to the electric dryer and cooked the film (the emulsion melted and ran off the base). Or the time Marty Lederhandler’s film of the Allied forces fighting in France was shipped via a confused carrier pigeon, which flew to Germany instead of England. When Lederhandler got to Germany two weeks later, he saw his pictures on the cover of a local magazine.

Around 1992, AP and Eastman Kodak agreed that, if AP would provide the specs and technical information and market the finished product, Kodak would build a digital camera. According to Bob Daugherty, who was with AP and is now retired, the first true digital camera was the NC2000 (NC stands for “news camera”). This was built on an off-the-shelf Nikon N90 body and a 1.3-megapixel sensor. The chip was smaller than a 35mm frame, so the viewfinder was masked down to size. This was done by etching the glass. The NC2000 had problems. Because of the long shutter lag, the photographer had to anticipate what was going to happen before it happened. If he shot a fire, the flames came out purple; if he shot water that sparkled in the sun, the highlights broke the image apart. But the camera did have a removable PMCIA Type III card. This was a small hard drive, six or seven times the size of a modern flash card, and it had moving parts. The camera weighed about three and a half pounds.

Another engineering problem was the non-removable battery. Once it got weak, it had to be plugged in and the photographer sat around while it recharged. At about $17,000 per camera, carrying a spare unit was prohibitively expensive. Images were shot in uncompressed RAW mode, so the card filled up rapidly. “And to start with,” says Daugherty, “the N90 Nikon was not industrial strength. Shutter leaves tended to blow and because it was an SLR, you couldn’t tell if the shutter was awry. If you used a flash, the camera usually overexposed. Once you shot an image, it had to be good enough,” he says. Additional shots “for insurance” were mostly out of the question. Despite the problems, digital was promising. The AP photographers were using the NC2000, but something dramatic was needed to get the hinges of history moving again. Finally, it came. The door began to swing shut on analog when The Vancouver Sun and The Vancouver Province newspapers in Canada bought 20 new digital cameras and announced they were giving up film. The new cameras took two frames per second and had a buffer of six. After that, the camera usually stalled.

But to photographers, it was like getting out of a horse and buggy and getting into a snazzy, new automobile. “You could shoot closer to deadline,” says Daugherty. Once the cameras were out in the field, improvements came with dazzling speed. AP realized no computer was then available to handle photographs. So they partnered with Leaf Systems and developed a computer tower they called the Leaf Desk, which could store photographs. AP gave every member of the cooperative one, and the analog door hinges slammed shut for good in news photography. Mighty Eastman Kodak acknowledged in 2003 that its analog business was in irreversible decline, and spent nearly $3 billion to switch to digital. It finally realized a profit—$16 million—in the last quarter of 2006, when for the first time it earned more from digital than from film and its other products. (Source: AP, as reported in The LA Times, Feb. 9, 2007.)

Digital Goes Mainstream

By as early as 1992, digital photography had morphed from a novelty into a reliable tool for journalists—even for those shooting in color! Greg Gibson should know, as his photograph of George H. W. Bush, Ross Perot and Bill Clinton during the presidential campaign debates that year was the first digital photograph to make the cover of a major magazine (Newsweek)— and it was in full color. In this same instance, it was also the first time a news organization had used a digital camera to capture the lead images on a story. Digital, prior to that, had only been used as a supplement. If it worked, great; if it didn’t, it was no loss. According to Greg, “This time we put all our eggs in the digital basket, so it had to work!”

The camera’s hard drive was “a big shoulder-mounted pack, like the old video camera decks,” Greg explains. After being used, the hard drive was shipped back to the darkroom for processing into photographs. Because he used a digital camera, Greg’s photographs were 30 to 45 minutes ahead of the other photographers using film. It was, he says, “all about speed, less about quality.”

On election night in Little Rock, AR, Greg and his team cabled the digital camera directly to a Macintosh Quadra 950 computer, located under the camera platform, with a ten-foot SCSI cable. The editor, located under the press platform, was able to see the images on the computer as the photographer above him shot them. Since the camera could only take one picture every two or three seconds, timing was crucial. The Associated Press submitted the images to the Pulitzer committee, and Greg shared the resultant prize with his colleagues at AP.

Greg was happy, he told himself—having moved into the cutting edge field of digital, capturing images of the famous and the infamous, working for a great company, getting recognition and working alongside great colleagues, doing what he had always wanted to do. But something inside him was coming to a slow boil as he clicked his shutter on one front-page image after another. After taking a picture of Monica Lewinsky outside the Washington, D.C., Mayflower Hotel in 1999 that won him his second Pulitzer, Greg says, “I had an epiphany.”

Over and over, we witness celebrities emerging from colonnaded buildings to rush off somewhere. The media scrum galvanizes. Shutters click like castanets. Strobes flash and microphones are poked into faces as photographers fandango for the main chance. Lewinsky could have gone down into the private parking garage in the building, slid into a limo with smoked glass windows and zoomed off without anyone being the wiser. Instead, her handlers frog-marched her across the street, surrounded by a dozen bodyguards, right into the throng of waiting reporters and photographers.

It seems that Greg had abandoned the frenzy of film processing in tense situations for the new, quick-snapping world of digital. “Photographing a 20-year-old woman crossing a street shouldn’t be so crazy,” recalls Greg. The whole process began to seem absurd, and Greg felt even more absurd “for allowing myself to be used in that way and breaking my neck in this photo scrum” to try and get the shot and send it off to his publication the fastest.

Still, Greg waited for the right moment, and when, for a brief second, Lewinsky was directly in front of him looking into the eye of his camera, he clicked the shutter. He sensed a winning shot, and so it proved to be. As Greg put it, “Some days it’s better to be lucky than good.” It was, he says, a difficult image to pull off. “It wasn’t a matter of just waiting till it came together,” he says. “It was a matter of managing the scrum, and getting into the right place at the right time. When you’re in it with 50 photographers, you can’t wait for anything. You have to make your own luck.”

When Greg took his photograph of Paula Jones in Washington, D.C., making your own luck was the rule of the day. Hundreds of press people crowded the scene as super-sized bodyguards scrimmaged to protect her from hard-charging photographers jockeying for the elusive, yet always available celebrity.

“With Paula,” Greg says, “I had deliberately taken a position opposite all the other photographers. She came up in a cab across the street from the stakeout with her husband. All the photographers gathered around the door she was sitting next to. We had another photographer there, so I went to the opposite side and was going to make a picture of her getting out of the car surrounded by all the media. The only problem was that there were so many cameras on that side of the car she couldn’t open the door. She ended up getting out on my side of the car. I was the only photographer there, and I was able to stay in front of her the whole time.”

Greg clicked the shutter on yet another winning digital shot. But again, a sense of unease welled up within him; repetitive, headline-producing reportage about uninspiring people was finally taking its toll.

Is That All There Is?

Doubt gave way to revulsion, and in 2000 Greg began a rigorous self-examination. He decided to take a sabbatical from photojournalism. His first move was to sell Pressroom Online Services, a company he had started in 1995, to Frontline Communications.

Overwhelmed by the rapid nature of news-gathering and reporting through digital imagery, Greg put his expensive cameras on the shelf and bought a Nikon point-and-shoot amateur camera. For the next two years, he took family pictures and what he calls “happy snaps.” He didn’t photograph much else until the day he met Matt Mendlesohn, who had worked with him at UPI. Matt, like Greg, had also left the field and begun shooting wedding photography. Greg was surprised to see that Matt approached a wedding as a photojournalist would—a story told with a camera. What he saw galvanized him and got him excited about photography again. Greg had already envisioned himself making the move to photography of this kind, given its family-friendly quality, little requisite travel and decent hours. With three growing boys at home, this was an important consideration.

Applying his enthusiasm, experience and philosophy, Greg quickly adapted his digital prowess and photojournalist’s eye into a role as a highly successful wedding photographer. And while he certainly left his mark on digital‘s popularization, he hasn’t looked back through the proverbial doorway since.

There’s More

As is obvious in the case of Greg Gibson, no matter the kind of photography you practice, the digital photograph is only the latest development in photojournalistic endeavors and wedding coverage alike. With new technology always on the horizon, who knows what will come next? Stay tuned, or you just might miss it.

Martin Elkort has been a photographer since age 10. He is a former member of the Photo League, and his photographs are in the collections of the New York Museum of Modern Art, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Museum of fine Arts, Houston. Elkort resides in Los Angeles, CA, where he continues to refine his craft.